Bang for our buck

How investing in local public services is foundational for growth

Investing properly in local public services is prerequisite for delivering economic growth to places across the UK and in ensuring that the impact of that growth is meaningful. That was the argument of Kickstarting economic growth: maximising the contribution of local council services, a paper that we collaborated on last year, with APSE and the University of Staffordshire.

Our local governments enable local growth directly – through activities to support economic development, regeneration, investment, skills provision and more – and indirectly – by improving how attractive their places are to investors and talent, and by supporting a healthy, mobile workforce through the provision of services like care and transport. The value this creates was no doubt considered in the recently announced Final Settlements for local government.

Since the publication of that first paper, we have remained in conversation with APSE and our collaborators at University of Staffordshire, thinking together about how we can expand on this work. At CLES, we’ve been looking at the demand side effects, specifically how the spend of local public services creates jobs and demand in the wider economies of the places they serve.

We’ll publish our full findings later this year, in an expanded version of the original paper which will include an update on the current context for local public services and case studies which will explore successful interventions by local authorities in reshaping high streets and town centres, investing in cultural and leisure provision and developing local plans which bring together housing, transport infrastructure, support skills and jobs.

“an important story”

For now, though, the findings that are beginning to emerge from our analysis of the demand side effects tell an important story at a time when the government is considering departmental budgets through the spending review process.

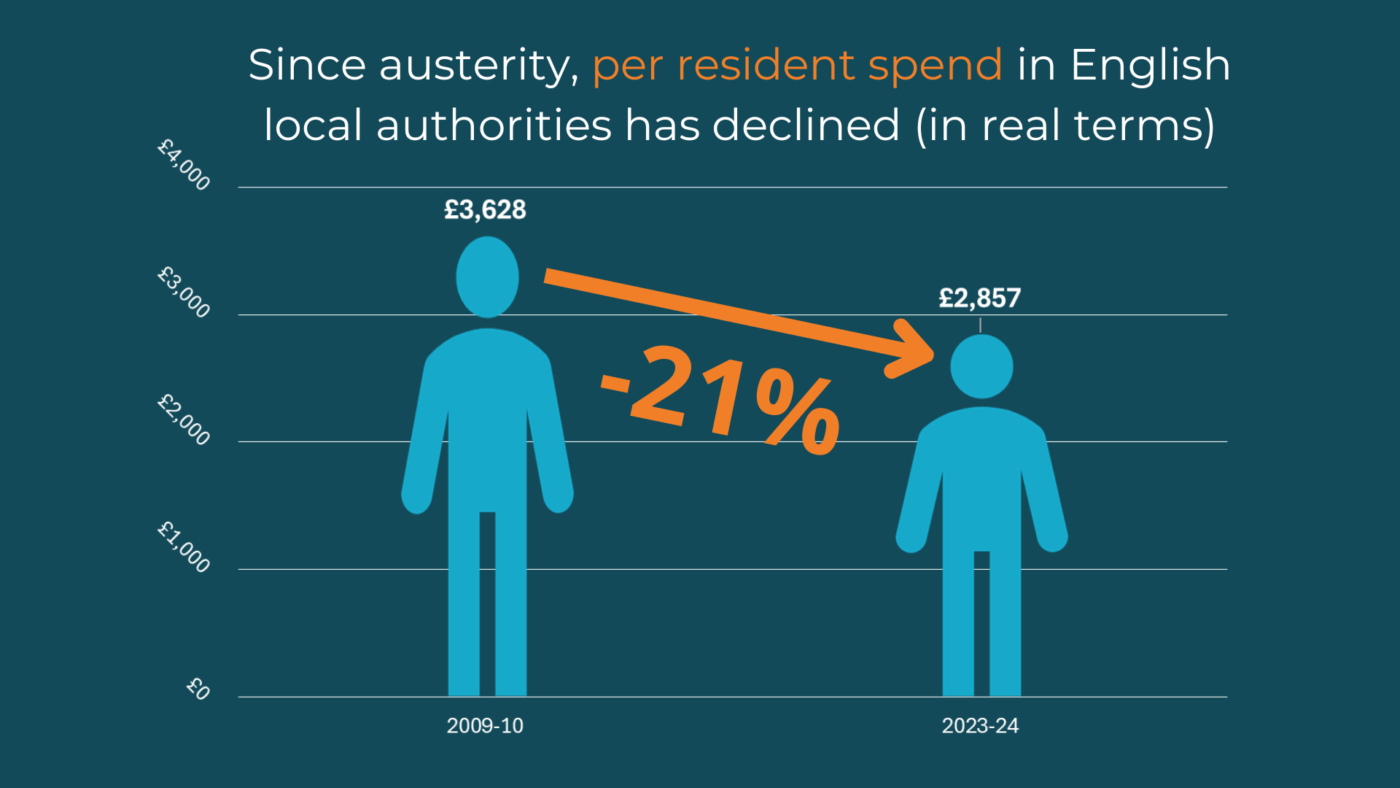

By using publicly available data we have been able to determine – in a shock to no one – that, since the coalition government’s austerity budget of 2010, central spending commitments to local government have consistently reduced in real terms.1 As a result, local government spending per resident in England has fallen dramatically from £3,628 in 2009-10 to £2,857 in 2023-24, or by 21%, after accounting for inflation.2

“for every one job created in the local public sector, another would be created in the wider economy”

We then looked at what would happen to the economy should that spend per resident on local public services (expanding our previous remit of looking at local government in isolation) be returned to 2009-10 levels. Our analysis showed that, not only would doing so create over 900,000 jobs (mostly in essential roles like the fire service, teaching and care), but that for every one job created in the local public sector, another would be created in the wider economy through supply chain effects and consumption expenditure by these employees.3

This would also contribute to growth – through the disposable income of employees, local government spending on goods and services and additional spend on running expenses – to the tune of GVA of £27.3bn.4 5 And this spend, too, goes further once supply chain effects are taken into account – we estimate a total direct, indirect and induced economic impact of £43.6 bn – a significant contribution to local and national economic growth.6

These are early findings but they demonstrate, none-the-less, the value of public sector spending and investment. The upcoming spending review should not only consider our local public services as the bedrock of a good society, nor simply as a tool by which we can encourage growth through investment from the private sector, but for its own contribution to the government’s flagship mission to support and promote growth.

1 We used official government statistics on local authority service expenditure, namely Revenue Outturn Service Expenditure Summary (RSX) data which covers England only: Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. (2024) Local authority revenue expenditure and financing. Link. Figures from the 2009-10 and 2023-24 financial years were compared, after adjusting for inflation using the government’s GDP deflator: HM Treasury. (2025) GDP deflators at market prices and money GDP. Link. We calculated spend per resident using population figures in England in each year: ONS. (2024) England population mid-year estimate. Link.2 Values are expressed in 2023 prices.

3 These “indirect” and “induced” effects are calculated using multipliers, which we calculate to equate to around an additional 890,644 jobs. A type II employment multiplier of 1.95 for public administration and defence was used to calculate the indirect and induced jobs. Source: Scottish Government (2024) Supply, Use and Input-Output Tables: 1998-2021. Link.

4 Direct GVA impact of the extra employee estimated by multiplying the number of extra employees (936,108) by their disposable income (i.e. less income tax, employee pension and NIC contributions). Average full-time salary in local government is £29,300. Local Government Association. (2025) Local government workforce data. Link. Average take home pay after 6.5% employee contributions to local government pension schemes, income tax and NICs is £23,082.

5 Consisting of £21.6bn from disposable income of employees and local government spending on goods and services, and £5.7bn direct GVA contribution from additional spend on running expenses.

6 This figure was achieved by applying a type II GVA multiplier to direct GVA contributions. The ONS does not provide type II multipliers for England. The Scottish Government’s type II multiplier of 1.6 for Public administration & defence was used which captures direct, indirect and induced GVA effects. Scottish Government. (2024) Supply, Use and Input-Output Tables: 1998-2021. Link.