Wonga’s demise is the tip of the iceberg in a rigged economy

Rather than seeing the collapse of Wonga as the end of the payday loan era we need to question the underlying factors that lead people to rely on such providers, writes David Burch and Matthew Todd.

Wonga did not collapse because of a lack of demand for fast credit. Instead, new regulations – such as limits on the daily interest rate and the total amount that borrowers could pay in interest and fees – created problems for its business model. Indeed, the macroeconomic factors that created the boom of payday lenders persists and there are worrying signs that, despite Wonga’s collapse, financial distress has risen – the number of people contacting the debt advice charity StepChange for assistance is at record levels, and the rate of personal insolvencies has also increased.

The growth of insecure employment

A principal factor in the continued crisis of Britain’s personal finances is the nature of modern work. This includes the growth of insecure employment. Research by the TUC finds that 3.8 million people – one in nine British workers – are now stuck in precarious forms of employment such as zero-hours contracts, low-paid self-employment or agency work. A feature of this type of employment is a degradation of traditional employment rights such as holiday pay, sick pay, payment for time spend travelling between calls, and regular shift patterns.

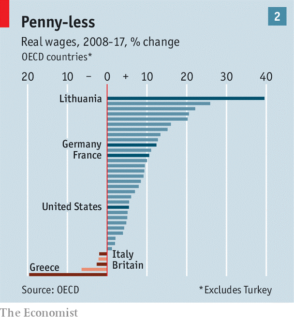

A decline in real wages

In addition, low pay is becoming increasingly prevalent. Economic theory states low unemployment causes wages to increase, however wages have done worse in Britain lately than almost anywhere in the rich world, as the graph by The Economist, below, illustrates. In part, this is caused by policies such as the public sector pay cap.

The demand for fast credit

The demand for fast credit is a multi-faceted problem, which requires action across all sectors of the economy. There are many approaches that would begin to address the underlying causes of demand for fast credit, these include:

- Reverse regressive welfare reforms – changes to welfare policy from 2010, including tougher rules on who gets benefits, and declines in their value, have played a part in low wages, because as losing a job becomes a scarier prospect, workers may not bargain so hard for better pay. Whilst some public pay caps have been lifted, punitive sanctions and caps on various benefits still exist, and leading to indebtedness, homelessness and in some cases death.

- Increase public and private investment – low wages are a factor of poor productivity, and Britain’s productivity is so low partly because we spend such a measly proportion of our national income on investment (17%), far lower than the world average (26%). By comparison, booming China spends 45%. This should be across both the public sector (transport, education etc) and private sector (technology, mechanisation etc). Once workers productivity increases, wages are sure to follow.

- Encourage unionisation and alternative ownership – employees in the gig economy have limited bargaining power when it comes to improving their working conditions, and employers can dismiss them easily. To redress the balance it is important that workers in private companies are members of a union and that alternative ownership structures, such as co-operatives and mutual, develop.

- Promote ethical sources of short term credit – many people still require access to fast credit, however there are sources which are not exploitative, such as credit unions and local banks. Indeed, there is news that the Church of England is consider leading a buyout of Wonga to prevent the debts of thousands of its borrowers being passed to another high-interest firm.

- Resource debt advice services and embed the skill of managing personal finances – there must be a real terms increase in investment in free or low cost debt advice services, that provide timely support and prevent minor debts escalating into financial crises. In addition, personal budgeting and financial education must be provided widely and throughout society – not part as ‘citizenship’ as they currently are, which lacks time and resources, but within GCSE Maths.

Unless the macroeconomic root causes of the personal debt crisis are tackled, demand for credit will continue and people will continue to suffer, with or without Wonga.