Deepening deprivation shows the need for the new economy

![]()

Where do you find deprivation in England today? The North? Coastal towns? Inner cities? The depressing answer found in today’s newly published Index of Multiple Deprivation is clear: everywhere.

Pockets of deprivation persist across the breadth and width of England. Little unites these places geographically – what they share is our underlying extractive economic model, unleashing a whirlwind of misery across this land.

“A staggering 88% of neighbourhoods that are in the most deprived 10% this year were also the most deprived in the last set of figures released”

Besides being geographically diverse, deprivation in England has become entrenched. A staggering 88% of neighbourhoods that are in the most deprived 10% this year were also the most deprived in the last set of figures released in 2015. There does not seem to be a significant improvement in large cities that have seen huge levels of economic, and so-called ‘inclusive’, growth. And whilst superstar cities still are rocked by huge deprivation, towns at their periphery, such as Oldham and Walsall are also becoming relatively more deprived.

Looking closely at today’s newly released IMD figures it is striking that of the top 10 most deprived LSOAs (Lower Layer Super Output Areas) based on rank eight can be found in the coastal town of Blackpool. As an increasingly prototypical example of a ‘left-behind’ town – beset by the ravages of neoliberalism – this should perhaps not surprise us.

A previous visit by CLES to Blackpool showed how a boy born there can expect to live nine years fewer than one born in Chelsea, whilst a recent report from the Financial Times demonstrated in detail the social pain afflicting the locality. In terms of migratory patterns, Blackpool is now a net importer of ill health, unemployment, and precarious labour, and a net exporter of good health and skilled labour.

“in Blackpool, over 30% of children are living in income-deprived families”

Today’s IMD figures paint a stark picture of ongoing social pain: in Blackpool, over 30% of children are living in income-deprived families, whilst more than a fifth of working age adults are suffering from income deprivation.

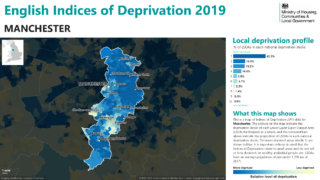

Conventional, orthodox economic analysis prescribes a heavy dose of inward investment as the solution to these problems. Yet the lingering presence of swathes of Manchester amongst the list of most deprived areas should disabuse us of this approach. Despite the preponderance of construction and continuing governmental bluster surrounding the Northern Powerhouse, Manchester is the 2nd most deprived Local Authority based on rank. Since 2010, it has been in the top five nationally; and it has been in the top 10 since 2004. Indeed, the proportion of LSOAs in the 10% most deprived nationally has increased in Manchester, up 2.5% from the 2015 IMD to 43.3%.

That this social pain is embedded and escalating across both hubs of agglomeration and the peripheries should send us a clear message – our economic model is not working. Places already struggling are being further hit; places ostensibly thriving are doing so in extractive and unjust ways.

Poverty is becoming locked-in, from big cities to coastal towns. We need to change our model of local economic development if we want to break out of this vicious cycle of deprivation and despair.

CLES commends the hardworking and committed individuals toiling day in and day out on the ground, in municipal offices, and in the charity sector – making a discernible difference in their communities. But a centralised state, extractive economic model, and the ravages of austerity all work daily to stymie their efforts. It does not have to be like this.

At CLES, we advocate an approach to local economic development known as community wealth building. It is working – as our recent report with Preston City Council shows. It is on the move – taking shape from Sunderland and the Wirral to Islington and North Ayrshire. And it is growing and flourishing, part and parcel of a new economic movement.

Based around five key principles – plural ownership of the economy; making financial power work for local places; fair employment and just labour markets; progressive procurement of goods and services; and socially just use of land and property – this is a tried and tested approach that brings discernible benefits to local people.

“By rewiring how and for whom our local economies function, we can bring about positive changes, and distribute ownership and control, rather than seeking to redistribute the illusory trickle-down gains stemming from inward investment.”

The entrenchment of poverty and deprivation is a problem that can’t be solved by the same economic strategies that exacerbated these issues in the first place. We need a new approach – and community wealth building is the practical, scalable, and democratic way to start building better local economies from the bottom up.